This is an edited excerpt from a paper I did on this topic. It involved my research of the discipline (history, background, and details), and personal use of the discipline, as well. I will be making a reference piece available that can be kept in one’s Bible, and used for personal or group purposes. (Please keep in mind the following is ©Lisa Colón DeLay, 2008, and cannot be reproduced in any form without my written permission.) If you wish to share this with others, please link here, or pass along the URL. Thank you.

Please enjoy!

And God be close to you.

Lectio Divina

(Lectio-pronounced: LEX-ee-o)

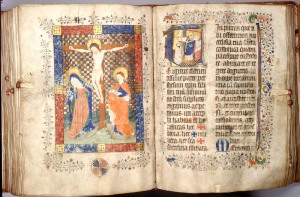

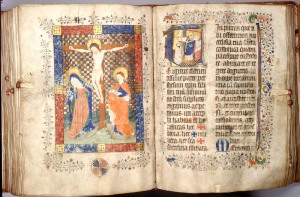

Lectio Divina as a practice harkens back into early Christianity, to the desert fathers and mothers who practiced meditation on biblical texts.[1] In about 220 A.D., Origen, an early church father, who first taught in Alexandria, and then later in Caesarea, extolled the advantage of combining Scriptural reading with focus, regularity, and prayer–hallmarks of lectio divina.[2] An Eastern dessert monk, John Cassian in the early fifth century introduced the practice to Christians of the West. The Cistercian monks have traditionally combined reading, study, and meditation of scripture through the ages.[3] In the sixth century monasteries that followed the Rule of St. Benedict formally practiced the discipline as a normal rule of daily monastic life.[4] Benedict of Nursia, Italy (ca. 480-ca. 550) left Rome for the village life of Subaico, and built monastery life around community, encompassing manual labor, prayer, and scared reading at worship, and at meals.[5] Of course, attention to Scripture, for followers of Yahweh, is nothing new. For millennia, Jewish tradition has been renown for valuing the copy and preservation of Scriptural texts, meditation on God’s scared Words, and Scripture reading as a normal part of public and private life. Christian tradition follows in this stream as well, with reverence for the Word of the Lord.

In the 12th century, Ladder of the Monks by Guigo II created a schematic pattern to lectio divina of four movements still commonly used: lectio, meditatio, oratio, and contemplatio.[6] Lectio divina has everything to do with listening. Whether we hear the Scripture when read repeatedly corporately, or we read it out loud several times, or we hear it in our minds, as we read repeat it–we are careful to listen. Lectio divina centers on reading and receiving from God. It also journeys into the contemplative tradition of Christianity as it involves much “prayer of the heart.”[7]

Lectio

The first movement of lectio divina involves lectio–reading the text. The text is usually not very long, and is most often Scripture. However, some also dwell on passages of spiritual writing, by devout Christians, to draw them to deeper thought, prayer, or devotion.[1] In this movement, one reads the text several times carefully with “wide eyes”, but also, with the whole mind. With active reading and awareness, one reads the text cognizant of God’s power at work through the text.

Meditatio

After a deliberate reading of the text, one moves into meditatio. St. Benedict mentioned that one listens to the Word of God “with the ear of the heart.”[2] In meditation one ruminates, or chews on the text–digesting it, and working it over. One may find an association, poignant word, or image on which focus. In this way, he or she receives from Gods Word. Some present day applications of meditatio exemplify an intellectual preference. They involve consulting commentaries, digesting relating liturgy, or reading relating texts to study the sacred text more fully.[3]

Jean Leclercq explains medieval universities, unlike monasteries, differed in their use of lectio divina. Scholastic students approached Scripture as an object to be studied and investigated by subjecting questions to the text. This seems analogous to some of our contemporary Evangelical tendencies. In medieval times, a scholastic pupil questioned himself to the subject matter, and he “sought science and knowledge” in his quest. These students sought discovery remaining more “objective, theological, and cognitive.” Monastic disciples were content to stay more “subjective, devotional, and affective” in their habits.[4]

Oratio

The meditatio movement flows into oratio–prayer that may be much like dialogue–both speaking and listening. Prayers of praise, worship, thanksgiving, supplication, confession, and so forth, may be a part of oratio.[5] Lectio divina ends in a contemplative phase, though it is sandwiched by meditative prayer and contemplative prayer. Some of this prayer is cerebral and responsive, but it gives way to “prayer of the heart.” Kenneth Boa describes meditative prayer as a more “intellectual exercise.”It engages us more actively as we become thoughtful, vocal, and imaged based compared to contemplative prayer.[6]

Contemplatio

In contrast with the meditative prayer of oratio, contemplative prayer is far more mysterious. One finds it in silence, and in the loss of activity and images. In this stage, one abides and receives from God with “interior stillness.”[7] The contemplatio movement of the lectio exercise exists beyond words. One may discover the deep knowing of the Almighty God who is within, as well as strength, comfort, and a rich and powerful feature of the discipline. Thomas Merton beautifully describes the conversation with God thus: “God takes care to provide [the soul] with everything it desires, and to such an extent that it often finds within itself a very savory, delicious nourishment, though it never sought nor did anything to obtain it, and in no way contributed to it itself, except by its consent.”[8]

This contemplative way is so reflective and quiet as to be rather counter-cultural, existing against our noisy and fast-paced times. In this movement, our thoughts dim, our intellect releases, and we rest in God’scomfort, presence, and power. Our hearts find him, and he fills our hearts. This contemplative movement is a passive way. Why contemplate God in such a way? Thomas Merton answers this question well in following quote:

“What is the purpose of meditation in the sense of “prayer of the heart”? In the ‘prayer of the heart’ we seek first of all the deepest ground of our identity in God. We do not reason about dogmas of faith, or “the mysteries.” We seek rather to gain a direct existential grasp, a personal experience of the deepest truths of life and faith, finding ourselves in God’s truth.”[9] As we center ourselves in God, we may more easily perceive Reality, as God is the source and the fullness of Reality itself.Practical uses in the contemporary church:

Tony Jones notes that lectio divina is gaining in popularity in contemporary churches worldwide.[10] Certainly within the Emergent church movement in North America, the practice has growing appeal, and a number of recent books have come out on the topic. Perhaps the postmodern love of mystery coupled with the renewed interest in ancient church practices has piqued the level of interest. Various contemporary churches are reintroducing the practice into facets of worship and prayer venues.

Lectio divina has various specific practical uses in the contemporary church, some of which have already been mentioned, such as devotional or inspirational Christian writing, group prayer and worship, and bible study. Sarah Butler notes the practice of lectio divina has allowed her to better hear the rhythm of the people entrusted to her ministerial care. The practice of listening and trusting God, in this way, has grown a deeper place in her heart for her people, and a greater compassion for them. She elegantly describes that lectio divina also increased the ability to experience “God’s embrace in the midst of suffering.”[11]

Gregory Polan explains that lectio divina is of particular contemporary benefit for spiritual nourishment in Eucharistic Liturgy at the “Table of the body of the Risen Christ.”He finds lectio divina exceedingly rich for the church to bring added meaning and reflection to this corporate event.[12]

This is only a small blurb on the topic Lectio Divina, and its uses and benefits. My experience of the regular practice of it reaped a spectrum of interactions with God from vivacious jubilation, poignant insights, and gentle comfort, to awkward silences, and even periods of dryness. I write about it now, not so one can inject another quick tactic into one’s life to see spiritual jackpot. In reality, the spiritual journey consists of varying terrain. I present this information now so those desiring to ready themselves more for God’s gracious work can yield and place themselves in a better spot for the seeds of grace he alone plants and nourishes.

If you have any questions about Lectio Divina, or would like to share your experiences (whether positive, or negative) I welcome your comments.

[1] Jones. The Sacred Way, 54.

[2] Gregory J. Polan. Lectio Divina: Reading and Praying the Word of God. Liturgical Ministry, no. 12 (Fall 2003): 203.

[3] Schneiders. Biblical Spirituality,140.

[4] Boa, 175.

[5] Schneiders, 140.

[6] Boa, 182.

[7] Ibid., 182.

[8] Merton, Contemplative Prayer, 40.

[9] Ibid., 82.

[10] Jones, 54.

[11] Sarah Butler. Lectio Divina as a Tool for Discernment. Sewanee Theological Review, 43:3 (Pentcost 2000): 303.

[12] Polan, 206.